Editorial | Volume 23 No. 6

Esteemed readers,

dear friends,

Do you like books? So do we. And do you like book reviews? Same here. But why does the German Law Journal hardly publish book reviews?

The reason is as mundane as simple. We lack the capacity to process them. It begins with the lack of the institutional backbone necessary for screening the wide range of subjects within our ambit of interest for exciting new appearances, to commission reviews and send out the books. True, each of our panel of Editors in Chief gets a fair quantity of requests to publish book reviews from authors and reviewers. However, we believe it is the task of editors to guide the selection process rather than waiting to watch ready-made reviews pop up in our mailboxes.

Moreover, space in our journal is a scarce resource. That might sound funny for an all-online journal. But paper is not the issue. Rather, it’s about the time of our wonderful editorial team at W&L University Law School in Lexington, Va. Book reviews have to be edited, revised, and so on. That would place a disproportionate burden on a team of highly dedicated, well-trained volunteers that shoulders eight to nine issues of our journal a year. (If you think you know the bluebook rules, they will disillusion you in a moment.) For these reasons, the board of the journal has decided that we normally do not publish book reviews.

Until we do. Regular readers may remember that we have used our editorial discretion in a number of rare cases to highlight works which we deem essential for sharpening the profile of the journal. Examples include a review of Günter Frankenberg’s recent works a few issues back.

Today is another occasion. May I introduce you to our new special issue vol. 23#6 on “New Private Law Theory” by Stefan Grundmann, Hans-W. Micklitz, and Moritz Renner. Connaisseurs of the journal will understand why we picked this particular work for an entire collection of reviews. In a way, it brings the journal back to our roots. Peer Zumbansen, one of our founding editors, has been a pioneer in the field of critical private law theories that understand law in the wider context of society. With his departure, that flank of the journal has remained somewhat open. A notable exception is the translation of Otto von Gierke’s Social Role of Private Law.

Moreover, we are sympathetic to the project pursued by the volume under discussion. Private law, the first thesis advanced in the book – and in the guest editors’ introduction – is pluralistic. In other words, new private law theory bodes farewell to the hegemony of the economic analysis of law. Admittedly, that hegemony has never been as strong on the European continent as on the other side of the pond. But the economic analysis of law got considerable clout from its affinity with neoliberal epistemologies. The pluralism of new private law theory comes with a penchant for comparative law – a passion it shares with the people behind the journal. Moreover, arguably the most interesting feature of new private law theory is its “application-oriented” character. Don’t suspect the desire to please practitioners behind this move. Rather, the authors propose that the various social sciences coalesce around the hermeneutic method. A useful reminder that despite the trend to empirical research, hermeneutics is still the key to understanding society. For the authors, society is not identical with the state, the fourth feature. This is one of the many ways how new private law theory allows critical inroads into private law, its fifth and ultimate feature.

This special issue assembles important critiques of the project. A first set of contributions addresses its methodological pluralism. Hanoch Dagan asks what holds new theory of private law together if it is pluralistic. In his view, the cohesive element is legal theory – the claim of all law to legitimate authority. Daniel Markovits sees new private law theory as a modern adaptation of the scholarly genre inaugurated by Christopher Langdell’s Selection of Cases on the Law of Contracts in 1871. He takes us on a comparative journey on legal scholarship as a science then and now. Giorgio Resta uses the aspect of disciplinary pluralism to question whether law is a social science, as the composition of ERC panels suggests. By contrast, Guido Alpa, drawing on the evolution of Italian private law, deems law as a social science that combines doctrine with interdisciplinary insights.

A second set focuses on issues of justice. Ralf Michaels scrutinizes new private law theory from a global perspective. While the global south is present in many of the cases discussed, it remains marginalized as a law-creator. This would call for a more radical pluralization. Simon Deakin argues that the role of private law in the social question in the 19th century resembles its present role in creating and sustaining power asymmetries in a globalized economy. Chantal Mak uses the example of the Shell Nigeria cases to show how communicative action and constitutionalization not only sustain the new private law theory, but may in fact serve as deliberative anchors of community building. Candida Leone considers the new theory of private law as a methodological cornerstone for sustainable legal education. For Martijn Hesselink, the pluralism inherent in new theory of private law’s design makes it a democracy rather than a theory, yet one that could be further developed into a democratic theory of private law. Marisaria Maugeri’s inquiry into different strands of ordoliberalism questions the dichotomy between U.S. law as promoting free markets and European law as chiefly generating solidarity – a perfect way to conclude this special issue from the point of view of an editor.

Last words for now: Our call for special issues is about to close on 31 July. Hurry up!

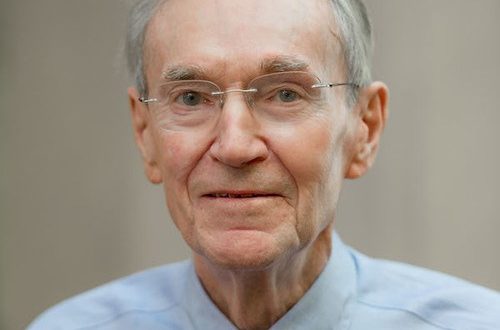

On behalf of the Editors in Chief,

I wish you happy reading!

Matthias Goldmann