Editorial | Volume 20 No. 2 & No. 3

Double Special Issue on

Populism and Constitutionalism

The bad news is that our teenage years are over – the German Law Journal turned twenty these days. The good news is that we do not waste this opportunity to celebrate. It is with enormous pleasure that we unveil to you a special gift marking our anniversary: a double special issue on populism and constitutional law: vol 20 #2 by Doyle, Longo, and Pin, and vol. 20 #3 by Blokker, Bugaric, and Halmai. By the way, the celebration will shift from the online world, our natural habitat, to the real world at our Symposium on Populism and Constitutional Law at the London School of Economics on 25/26 April 2019.

On the one hand, the topic of this double special issue and of the Symposium epitomizes the origins and programmatic orientation of the German Law Journal. Most importantly, the special issues adopt a comparative perspective that reaches beyond the surface of the black letter of the law and takes account of the historical, cultural, and social embeddedness of the law. “Deep law”, if you want. At the same time, this perspective is non-parochial and seeks to entice self-reflection rather than self-celebration. In this sense, the German Law Journal, notwithstanding our long-standing habit of tracking legal developments in Germany, has been as much about Germany as the Harvard Law Review has been about Harvard.

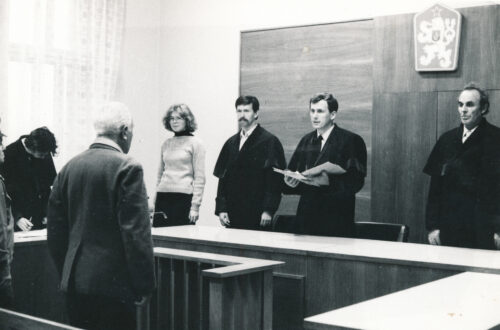

On the other hand, the topic invites us to look back in awe and bewilderment like a millennial watching their childhood on a magnetic videotape. The sepia color, far from arousing any sense of nostalgia, reminds us how far we have moved away from the context of our cradle. In 1999, transnational euphoria was still in full swing, and critics of globalization were just about to catch the eye of a larger public. Many of their concerns seemed entirely hypothetical, including to the legal discipline. Hence, the latter saw multiple calls for a new transnational law, occasionally connected to calls for the demise of the state, or at least for stateless law. Many took for granted the progressive effects of constitutional thinking in international, European, and private law alike. The German Law Journal is guilty as charged, having participated in both the movement and its counter-movements, such as the turn to critical histories and postmodern scholarship.

I believe that this legacy, and the ambiguity it creates for our understanding of the law, is now at the heart of current debates about populism and constitutionalism, as the two special issues, edited by Oran Doyle, Eric Longo, and Andrea Pin (issue 20.2), and Bojan Bugaric, Gábor Halmai, and Paul Blokker (issue 20.3), amply demonstrate. Both special issues pursue three questions, which Rosalind Dixon identifies in her introduction to issue 20.2: What is the relationship between populism and constitutionalism?; Did constitutionalism contribute to the rise of populism?; And which means of redress might constitutionalism have on offer?

Concerning the definitional question, most authors agree, albeit to different extents, that strict dichotomies between populism and constitutionalism are problematic. As Oran Doyle, Erik Longo, and Andrea Pin elaborate in their reaction to issue 20.3 (we asked each team of guest editors to react to the other special issue), a binary distinction between populism and non-populism (encouraged by popular definitions of the phenomenon in the political sciences), or populism and constitutionalism, risks entrenching the populist narrative of “us, the people” against “them, the elites”. Zoran Oklopcic even points to the responsibility of legal scholarship for “staging” populism as a bugaboo, a pretext for deflecting from deeper problems in constitutional regimes. Paul Blokker, Bojan Bugaric, and Gábor Halmai in their introduction to issue 20.3 therefore call for more granular historical and contextual analyses. In this sense, Kim Lane Scheppele provides a meticulous account of the ideological mindset of Hungary’s Fidesz party, drawing on the writings of Orban’s chief spin-doctor Lanczi. Gábor Halmai dissects the authoritarian character of Orbán’s regime, which used religion and the nation as covers for the nearly complete dismantling of effective checks and balances. Mark Tushnet demonstrates the blindness of a concept of populism that glosses over crucial differences between left-wing social welfare populism and right-wing xenophobic nationalism.

Regarding the quest for constitutionalist causes of populism, Eric Longo connects the well-established democratic deficit of supranational institutions to the rise of populism, while Andrea Pin and Gonzalo Candia carve out the responsibility of courts, in particular by promoting integration by law in Europe, and by doing too little too late in Latin America. Julian Scholtes argues that a truncated, legalistic understanding of constituent power lies at the heart of the ineffectiveness of the tools of militant democracy. Théo Fournier describes how Orbán in Hungary and Le Pen in France divert constitutional means to unconstitutional ends. In the case of Japan, Satoshi Yokodaido finds constitutional ignorance by the political elite, rather than constitutional overkill, to bear the responsibility for dwindling faith in the constitution.

Being so closely associated with the rise of populism, it would appear rather difficult for constitutionalism to come up with a cure. Nick Barber proposes reinvigorating political parties – a point to which Paul Blokker suggests in his response to issue 20.2 to shift the function of political parties to other actors. Possible candidates might include transnational movements advocating inclusive forms of populism, as Paul Blokker elaborates in his own contribution. In any case, relying on courts and adjudication might be counter-productive, as David Prendergast argues. Oran Doyle, relying for that purpose not without irony on the constitutional theory of the alt-right’s patron saint Carl Schmitt, proposes dissociating the concept of constituent power from any reified, pre-constitutional idea of the people. Ultimately,Bojan Bugaric points to the Elephant in the room, the constitutional entrenchment of austerity, and calls on lawmakers to adopt policies fostering, rather than defeating, solidarity among the peoples.

In the end, it is therefore not all doom and gloom. The double special issue combines sobering analyses with carefully dosed glimpses of hope for our current predicament. You will certainly have your reservations, objections, and suggestions. Bring them to London and join us on 25/26 April. Or bring them on paper and share them with all our readers. It is this community of readers/authors to whom we are immensely grateful for their support during the past twenty years. We hope very much you will continue reading, writing, and bearing with us, in good times and in bad, at least for the next twenty years.

As always, happy reading!

Matthias Goldmann

On behalf of the Editors